Voting

Enslaved and free Blacks voted for their own representatives in eighteenth-century New England. 150 years later, Black women in New England were fighting for voting rights, too. The struggle continues.

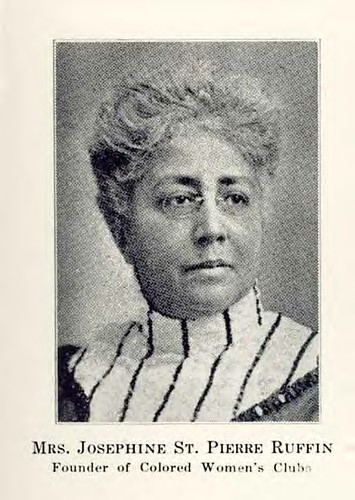

I published an article in Historic New England magazine that explores African American women's roles in the New England suffrage movement. I focus on activist Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, from Boston, Massachusetts. I still have more to say about this trailblazing woman! I came across an interview she gave in the 1890s describing the trauma that she experienced as one of the children who desegregated Boston's public schools. The parallel between her experience and the experience of Ruby Bridges in the mid-twentieth century is striking. There's no doubt in my mind that Ruffin's experience desegregating Boston's public schools shaped her fight for racial justice and suffrage.

You can read my article, "Abolition, Suffrage, and the Activism of Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin" here.

In the article, I also quote Charlotte Rollin, a Black activist from South Carolina. In an 1871 speech, she explained why women's suffrage was so vital:

We ask for suffrage not as a favor, nor as a privilege, but as a right based on the ground that we are human beings and as such, entitled to all human rights.

It's such a potent remark about humanity and human rights – one that was repeated, actually, throughout the long nineteenth-century by many African American activists aligned with various causes. Indeed, these activists used the term "human rights," to talk about the emancipation of enslaved people, the rights of free Blacks and Indigenous people, and to demand voting rights for all citizens. For some, both abolition and suffrage were allied causes, so it makes sense that activists invoked the term.

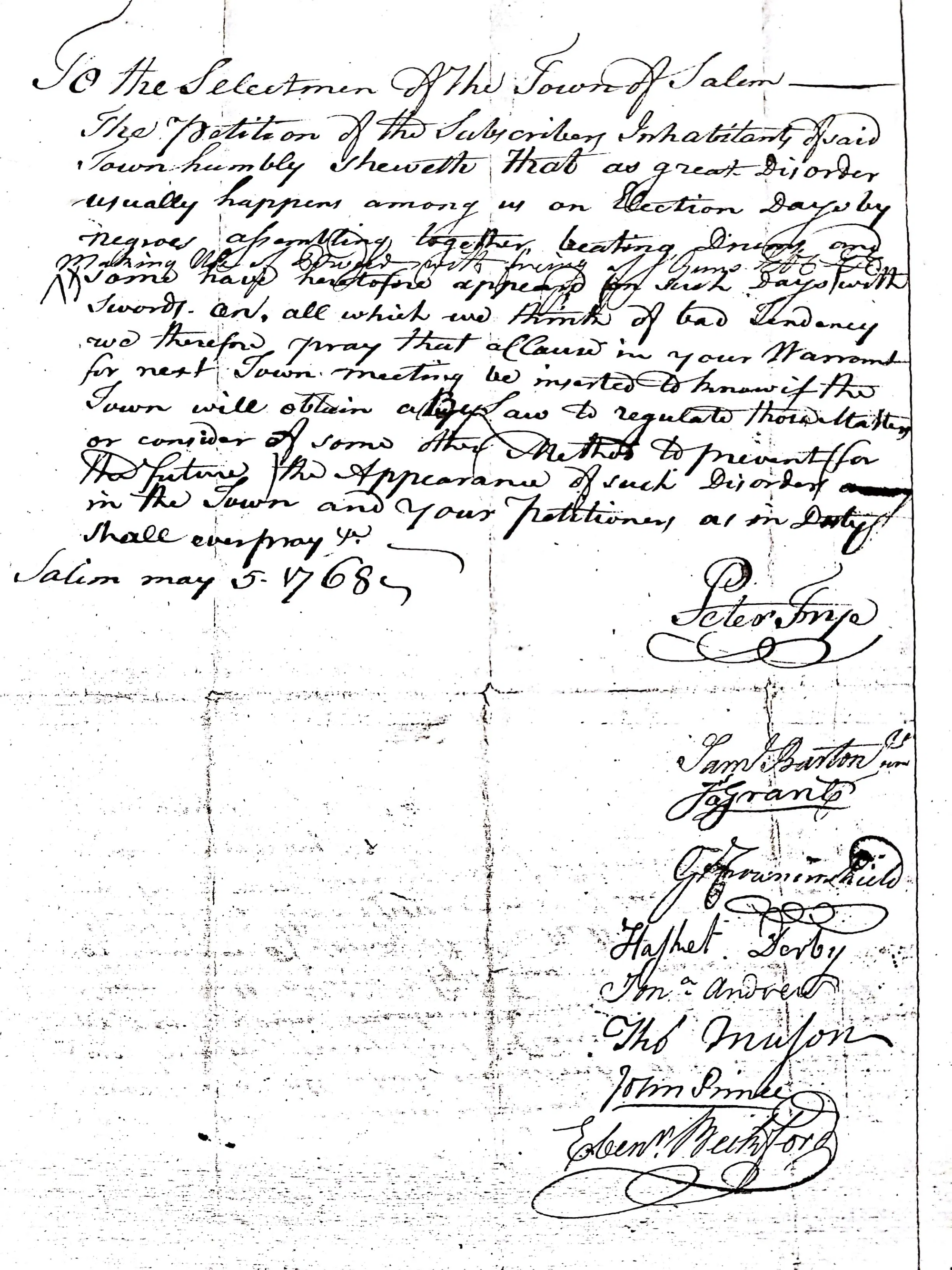

I just wrote a short piece, "Juneteenth and More: Celebrating Black Regional Civic Holidays," which explores the history and legacy of Negro Election Day, a civic holiday born in eighteenth-century New England. In this piece, I'm making a simple but important point: enslaved and free Blacks voted for their own representatives. It was ceremonial; it was fleeting. But it also gestured toward a future whereby Blacks would have full voting rights not just in their own communities, but in state and national elections too. This is an incredible history of Black civic activism, and we ought to commemorate it.

What Juneteenth is to emancipation, Negro Election Day is to voting.